LONDON: Crises are not new to the Japan-China relationship, but their impact only grows. There is little reason to hope for a quick resolution to the current one. The last crisis was long-lasting, begun by a drunken fishing trawler captain and ended with an awkward handshake between Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō and Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2014.

There is much to fear in that today’s crisis will escalate further. This crisis pits Japan’s security goals against China’s longstanding desire to reclaim full control over Taiwan. Finding an exit from these tensions will, at the very least, take time.

Diplomatic crises often change the stakes for each, and for the Japanese, the consequences of this crisis are multifaceted. Japan’s new prime minister, Takaichi Sanae, was the initial focal point. As the Washington Post editorial board aptly noted, she said the “quiet part out loud” when she responded to an opposition party lawmaker’s question in the Diet, acknowledging that China’s use of force against Taiwan could be seen to threaten Japan’s survival. In official Japanese government speak, that means that Japan might have to order its Self-Defense Forces to respond with others.

The Chinese government responded in various ways. The Consul General in Osaka on X claimed that those who stick their neck in the affairs of others could have it chopped off, an indelicate threat given his diplomatic status. But the real response came from Beijing. Chinese tourists and students were warned against travel to Japan, ostensibly for their own safety. Then, Japanese aquatic products were once again banned under the guise of health and safety. Economic consequences were to be felt by the Japanese people.

Out in the waters of the East China Sea, the longstanding contest over sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands, as they are called by Japan, or the Diaoyu Islands, as they are called by China, resurfaced. Several incidents have been reported in which the Chinese Coast Guard vessels have challenged Japanese fishermen, only to then be confronted by Japan’s Coast Guard. Out of sight, these incidents are reported by each government differently, but it suffices to say that this is a dance that carries considerable risk. A direct challenge between the coast guards of each nation could easily lead to further escalation, including the introduction of military forces. Keeping escalation of this sort at bay is essential.

The day-by-day, blow-by-blow escalatory dynamics define a crisis, but they do not always reveal the consequences of that crisis. Diplomats and political leaders are tasked with managing incidents and the reactions of other states. The underlying tensions that lead to crises, however, must also be considered.

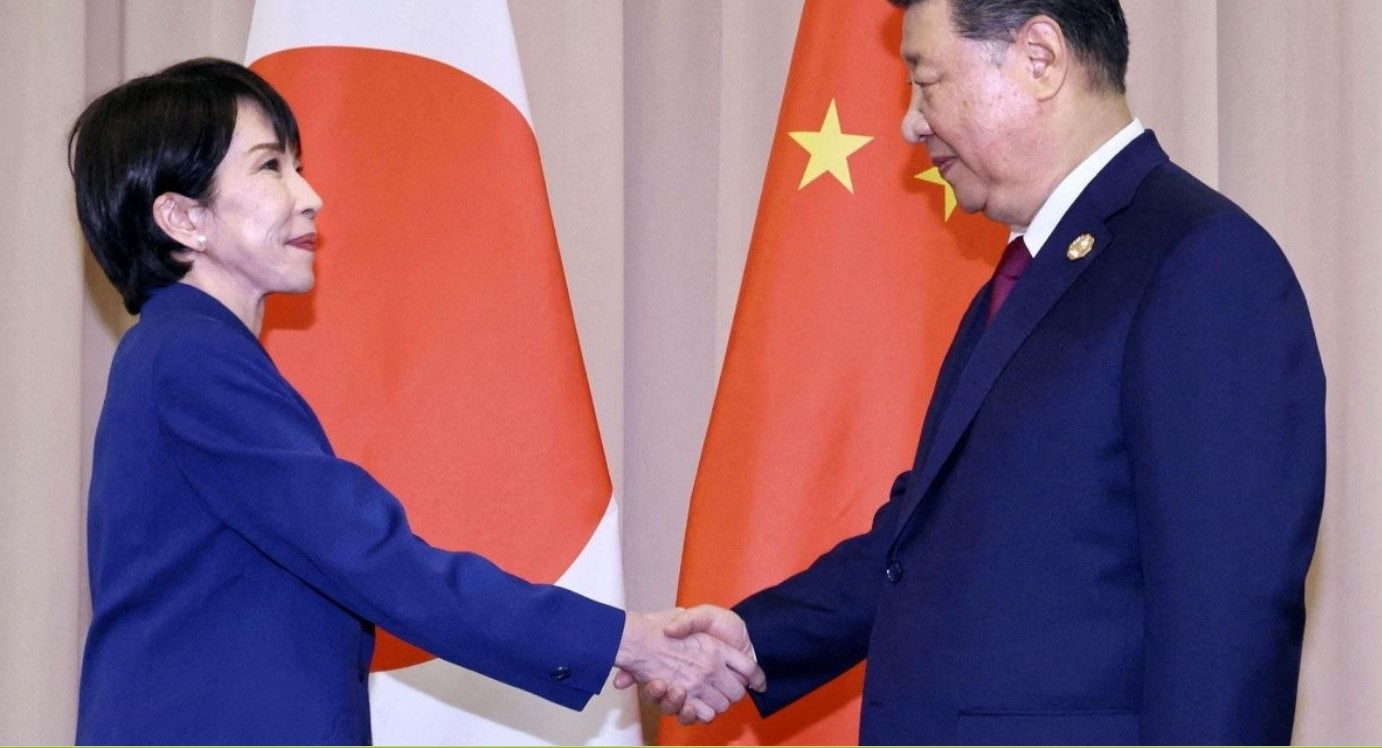

Why do Japan and China find themselves in these recurrent crises? Simply put, it is because their interests are in conflict. Where once Japan and China could resolve most of their bilateral problems through compromise and innovative policy change, today these two powers find it difficult to find common ground. I wrote a book in 2015 about this changing reality and bilateral difficulties have only grown between Tokyo and Beijing. By then, the two neighbors had confronted each other over their sovereignty dispute, sparking the arrests of a rebellious fishing trawler captain and his crew in 2010, demonstrations in both countries, the stoppage of much-needed rare earth shipments to Japan, diplomatic contests in the UN, and the purchase of the islands from their private owner by the Japanese government in 2012. Not until Abe Shinzō traveled to Beijing for the APEC Summit four years after the crisis began, did the real effort at diplomatic healing begin.

The consequences of that earlier crisis deserve attention as today’s crisis unfolds. Those consequences for Japanese politics and policy are multifaceted. First, the political fallout within Japan was significant. The Senkaku kiki, or crisis, seriously hampered the governing party’s credibility. The inexperienced Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was widely perceived as unable to defend Japanese interests and too inept in diplomacy to be trusted with running the country. The party is gone now, too damaged electorally to make a comeback. In 2012, the Liberal Democrats swept back into power under the leadership of Abe Shinzō and went on to eight years of repeated electoral success and a supermajority in the Diet. Abe is well known for his strategic revamping of Japanese policy in the face of China’s growing military muscle. Indeed, it was Abe who reinterpreted the Constitution to allow for the SDF to work with other nations should Japan’s survival be threatened—the very issue under discussion in the Diet when Prime Minister Takaichi made her remarks. What some do not know is, he was intent, as was his father, who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs at an earlier crisis over the Senkaku Islands, on ensuring Japanese control over its territory. Politics shifted on the islands, but also on the need for Japan to prepare itself for a test of its defenses.

Second, and not unrelated, the island crisis also changed the way Japanese viewed their security relationship with the United States. For the first time since the U.S.-Japan alliance was revised in 1960, China-Japan tensions suggested the possibility that Tokyo could find itself on its own as the target of hostilities. Up until that point, most Japanese thought that they would be involved in a conflict as a result of a U.S.-led operation, most likely on the Korean peninsula. Few imagined the use of force against Japan by neighbors, but China’s growing maritime power, the continued legacy of Japanese imperial ambitions, and the World War II invasion seemed a combustible mix in that Senkaku crisis. Ensuring U.S. support should another incident erupt became a priority of diplomats and defense planners alike.

Finally, the economic ties that had underpinned Japan’s relations with China since normalization in 1978 had fundamentally altered. Economic interdependence had long been seen by government and private sector interests in Japan as both commercially and politically stabilizing. From the provision of massive aid packages in the first two decades of the relationship to more strategic investments in China’s massive economic transformation, Japanese interests were well served by this relationship, even as moments of political tension flared. Yet a now affluent China can claim leverage over these very same interests, and Japan is far more vulnerable to decision-making in Beijing. For some time now, Japanese companies have lowered their profile in China, diversified their economic investments, and aligned with their government’s new interests in economic security measures to limit exposure to this threat. The use of economic retaliation was central to the Senkaku crisis, and it is even more conspicuously the tool of choice for the Chinese government today. Lessening Japan’s exposure to it is now part and parcel of private sector deliberations as well as government policymaking.

However this current episode of crisis ends, it will have ripple effects that go far beyond the policymaking of the moment. To be sure, avoiding any steps that could lead to the use of force by either country is paramount, and to date, while Chinese Coast Guard ships flirt with confrontation near the Senkakus, neither government seems inclined to escalate in that direction.

Politically, however, Japan’s prime minister is getting more credit than her DPJ predecessors for her handling of the situation. According to a Nikkei/TV Tokyo poll, her approval rating remains high at 75 percent, and 55 percent of those polled think her remarks in the Diet were appropriate. Ambiguity has characterized Japan’s formal statements on Taiwan in the past, but increasingly, more Japanese seem to believe that their security policy needs greater clarity.

Strategically, the Takaichi Cabinet had already decided to review its National Security Strategy and defense plan in 2026, and this crisis will undoubtedly provide fodder for ongoing efforts to strengthen Japan’s ability to manage crises and, if necessary, threats. Already, economic security measures are being put in place that will affect Chinese investment in land and real estate in Japan, and this will likely accelerate those. Japan is likely to continue to invest more of its GDP in its defenses, and next year’s strategic review should reveal how fast—and in what ways—Tokyo wants to increase its hard power.

And, finally, Japan’s diminishing appetite for economic interdependence with China is likely to drop further. Investments in China are likely to be affected. Diversification of markets for seafood and other aquatic products will continue, but so too will efforts to shore up supply chains so as to make them less vulnerable to Chinese government decision-making. Already, Tokyo has concluded an agreement with Washington to cooperate globally on the supply of rare earths and critical minerals. Japan has other economic partners with which it will likely find greater common ground and already is working closely with a host of partners in the Indo-Pacific and Europe.

The risks of this Japan-China confrontation should not be underestimated. It is not simply another spat. The United States will need to ensure this crisis does not escalate and will want to help find a way out of the current tensions. The phone call placed by President Xi Jinping to President Donald Trump demonstrated how complex U.S. involvement could be in this current crisis. An eye on the long game is what’s needed, however. Standing with an ally in crisis earns greater opportunity for future cooperation. Ignoring allies need for help could also have future consequences.

A crisis, or worse yet, a conflict across the Taiwan Strait portends a major power contest of a magnitude Northeast Asia has not seen. Deterring such a conflict will require a close and confident U.S.-Japan alliance. Crises may become a more regular feature of Japan-China relations as Beijing seeks to shape Japanese preferences over Taiwan. Without a doubt, this crisis will shape Japanese attitudes about the inevitable crises that lie ahead, and the U.S. too will need to consider not only the crisis of the moment but those to come.